Why an 80kg ray is so amazing.

August 4, 2020

August 4, 2020

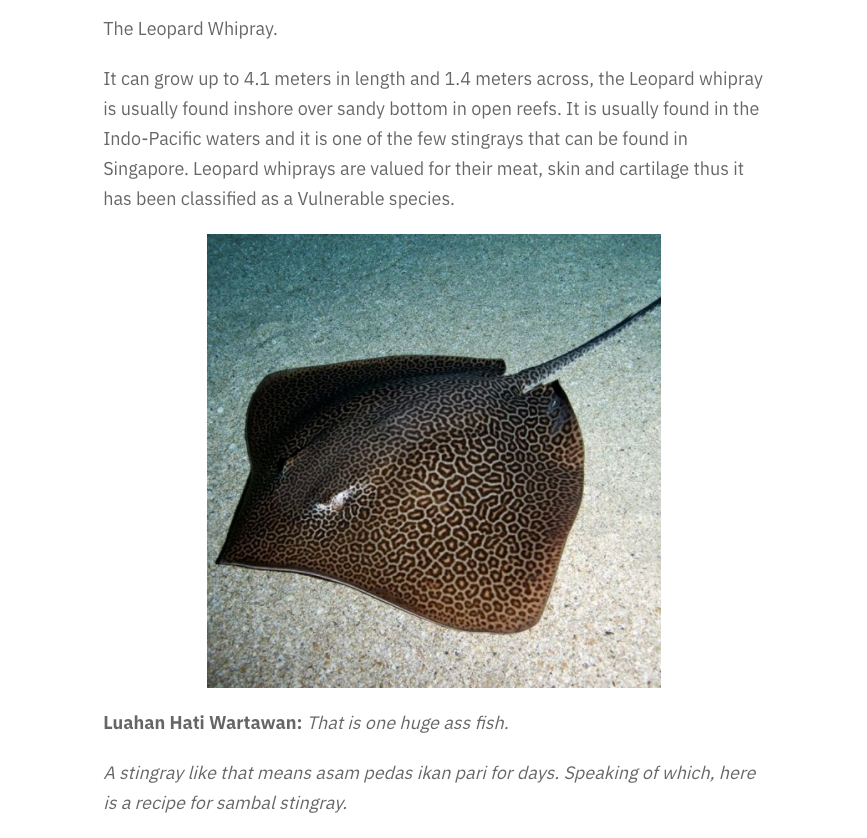

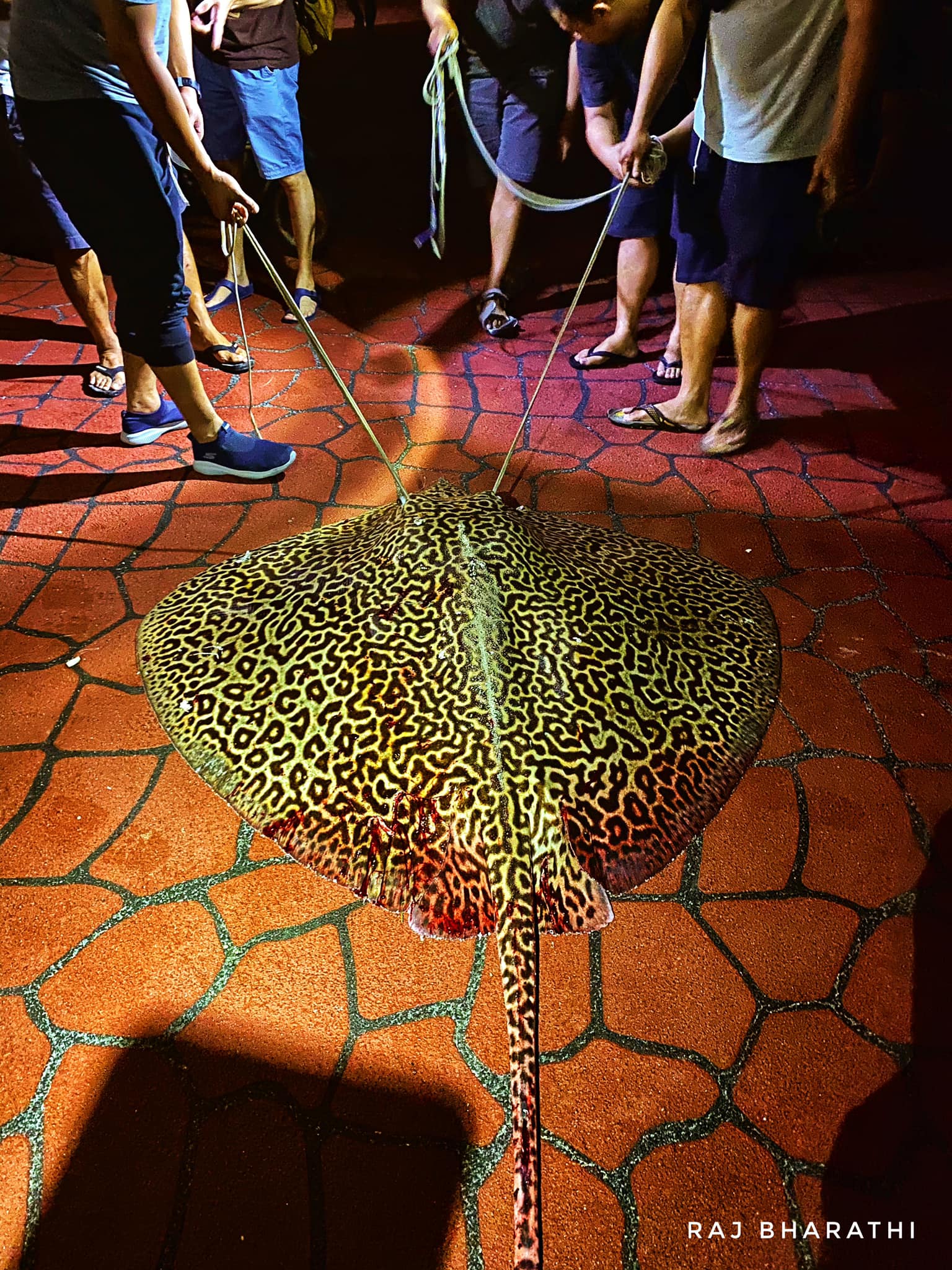

A large honeycomb ray (Himantura undulata) was caught off Bedok jetty last week. It was described as the 2nd largest catch from that fishing spot, and the largest haul by a “shorewrangler” this year. According to various blogposts, the ray had a wingspan that measured between 2-3 meters and weighed somewhere around 70-100 kg (I’m going with 80kg).

Almost every website that reported the catch had the fisherman, Uncle Alo, a “shorewrangler”, at the center of the story. Rightfully so. Uncle Alo had been fishing for many decades and I imagine he would have many good stories to share of fish he had caught, fish that got away, and certainly, days where no fish showed up. However, none of the posts that I had read about the big catch delved into either of those stories. Almost all included a line or two about the ray – which was supposedly an amazing catch. It would seem that the catch was “amazing” because it took three hours to yield to its fate (other websites said it was four hours). To understand just how amazing this catch was, we need to look at the events that led up to the ray hauling up at Bedok jetty on Jul 31, 2020. Think about it as an “Air crash investigation” – we can only see how miraculous the end of the story was until we understand how the events slowly unfolded and the odds stacked up.

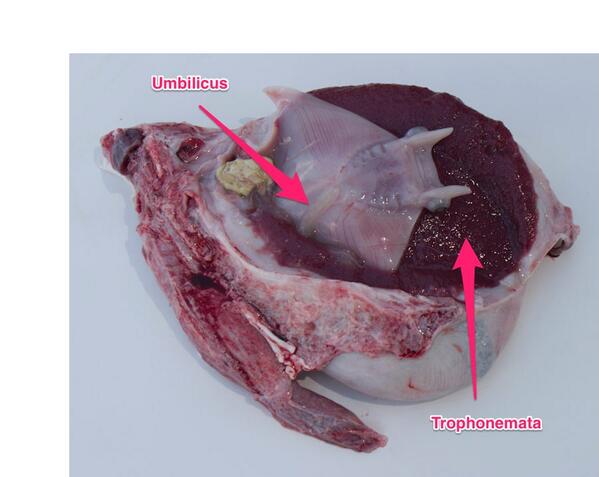

This ray was born live and received milk from its mom

Mother honeycomb rays carry their young for twelve months before giving birth to them live. Twelve months is about the same gestation period as a horse, a camel, and a donkey. Compare this to nine months in a human. Why would a ray do this? Why not lay them as eggs like bamboo sharks and be done with it? Well, there are some benefits. One of which is that the babies can be born quite “large”. It’s still only about the size of both your palms put together (i.e. 21-28 cm) but that means they are born too big for most other fish on the reef to eat them. If you think of camels, horses, and donkeys, the young are born pretty capable. They are big, and they can run. Of course they could still get hunted and eaten by a predator, but if they can run, they’ve got a good chance at life. Similar for the honeycomb ray, the bigger you are born, the better a chance you have to survive. Especially since the main predator of these honeycomb rays are sharks. But being born big can have some disadvantages. Spending such a long time inside the mom to get so big means that you can’t have a lot of siblings. Honeycomb ray moms give birth to 3-5 pups after a twelve month gestation. This long gestation also takes a toll on the mom, which nourishes the developing embryos with uterine milk (histotroph) that is absorbed by the embryo through vascular tissue (trophonemata) that surrounds the embryo. Nevertheless, it is a survival strategy that has worked for the ray so far. Which brings us to our second part.

Honeycomb rays are vulnerable, but not because they are tasty.

Honeycomb rays are vulnerable because they are long-lived, have few young, and are slow to sexually mature. Of the five pups that are born after a year-long pregnancy, probably one will survive. That’s OK if mom lives a long time. Think of mice and elephants – Mice have short lives, give birth often and have many young each time. Elephants take a frustratingly long time to grow and have few young in their lifetime. But they can live a long time.

Honeycomb rays are more like elephants than they are like mice, and I’m not saying that just because they can get big. Honeycomb rays take four to five years to reach sexual maturity. That’s 8 to 10 times longer than cats and dogs that are sexually mature at around six months. When honeycomb rays are born, they wander the shallow sea in search of small fishes, crabs, molluscs, worms, shrimps, and sea jellies while avoiding getting eaten by anything that is bigger than it (there are a lot of animals in the sea larger than a young honeycomb ray). They have to do this for half a decade before they are able to reproduce. If after 2000 days of wandering and evading the dangers of the shallow sea, it is still alive and has managed to find enough food to grow well and sexually mature, and if it finds another mate who has been able to do the same, they will mate. If the mating is successful, she will get pregnant and have pups a year later.

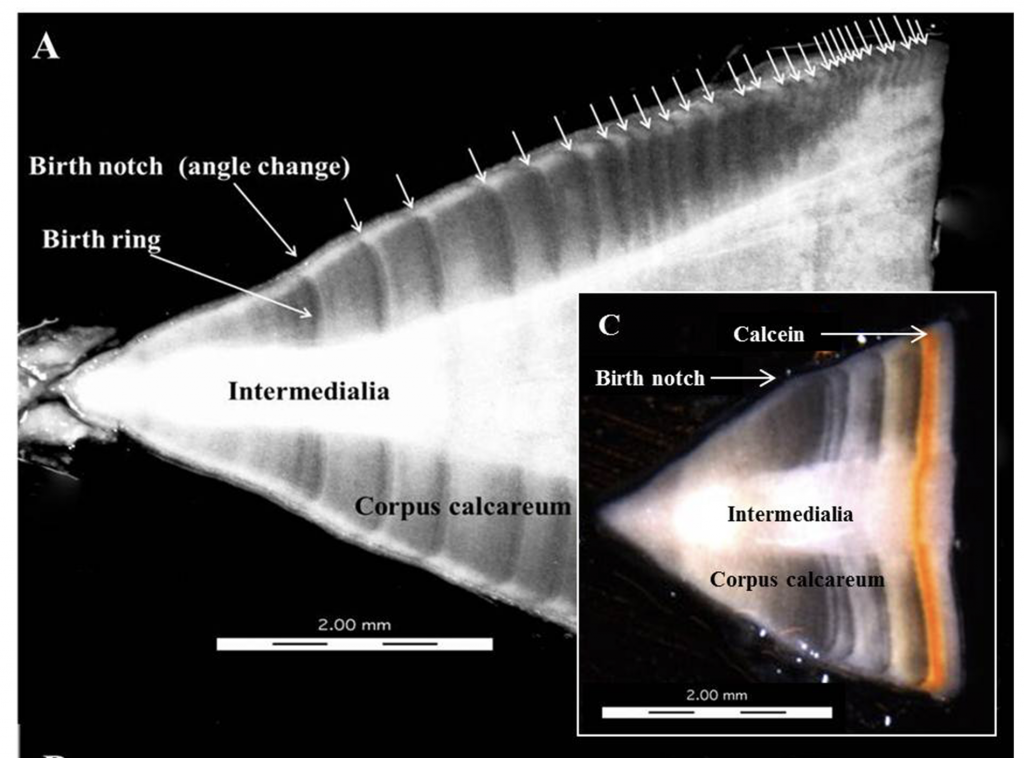

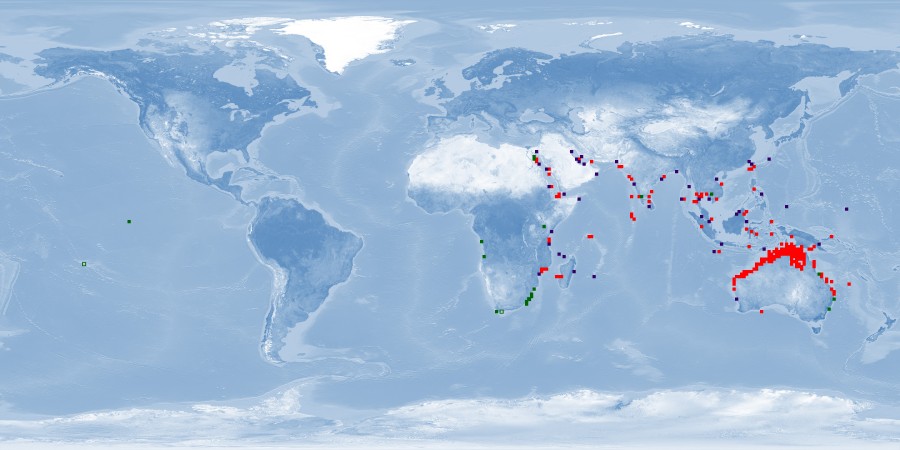

How old was the ray that was caught? It’s hard to tell once they reach their maximum size. If the ray caught at Bedok jetty measured 120cm in diameter, it could have been at least 9 years old. Surviving for 9 years is a great feat for an animal that lives in the shallow seas of the Pacific and Indian Ocean. Honeycomb rays may have a large distribution, but this distribution also overlaps with some of the most threatened coastlines in the world that are being reclaimed, dredged, developed and trawled. Honeycomb rays are a common bycatch in shallow sea trawling. Any ray that has managed to overcome the surmounting challenges of living in these shallow seas deserves a eulogy – hence this blogpost. This is the story of every honeycomb ray that was ever caught and landed. Nine years may seem a long time for a wild animal, but these rays are known to live for at least a quarter of a century in the wild. At nine years old, the ray would have been sexually mature for 4 of those years. If the ray was a female, she could have had four litters. Which brings us to the third part of this story.

The ray that was caught was likely a female

One of the first things I noticed when I saw this photo of the ray upside down was that it was a female, but I wasn’t really confident because the photo wasn’t really good. I felt a bit more confident after looking at the photo below that was photographed from the rear.

Male honeycomb rays would have stout claspers, which seem to be absent in this ray if we go by these two photos. Females are precious to any population, because they give birth to the next generation. Especially if the species is slow to sexually mature, have few young, and is long lived. To me, this is why this 80 kg ray was so amazing – her story. As I had looked through the blogposts and websites that reported the news of this haul, I felt disappointed that none of the sites gave more information about this magnificent ray, which is well-known for its ability to give hook and line fishers a good fight. I decided to deal with my disappointment by writing my own post to tell the other story about that big fishing event so that we can at least learn something about these animals that call Singapore shores home.

It’s wonderful to know and learn that there are such beautiful animals that live in our shores. By protecting our reefs, we can ensure suitable habitat for these animals to hide when they are young, feed so that they may live, and live long enough so that they can mature, have young, and continue to provide joy, excitement, and awe for fishers and non-fishers alike. The few photographs of this fishing event taken by spectators can tell us a lot if we try to ask some questions. There is so much beauty and wonder hidden in our murky waters.

Posted in

Posted in

content rss

content rss

COMMENTS