Singapore’s Seahorses – Sex, soup and sleep

August 4, 2018

August 4, 2018

By Aidan Mock: When I first started conducting research for this article, I googled ‘Singapore seahorse’ to get a feel on whether Singaporeans associated this noble sea steed more with the oceans or with traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). However, it came to my surprise that the top hits were related to neither option . Instead, it appears that Singaporeans primarily associate the wondrous seahorse with … sleep.

Unfortunately the seahorse logo itself is inaccurate (seahorses generally curl their tails forward not backwards) but perhaps that is the lesser crime in this image.

In an attempt to correct this egregious but forgivable association, I write about the seahorses that live on Singapore’s reef: who they are, what they do, and why they aren’t any better for your body despite what TCM medicine advocates would want you to believe.

Biology

All seahorses belong to the genus Hippocampus, which is a mashup of the Greek word hippos that means horse and kampos that means sea monster. An apt name for an organism that looks like it popped right off the pages of a fairy tale.

A tigertail seahorse (Hippocampus comes) from the Hantu reef. A human-sized seahorse would probably be the stuff of nightmares (Photo: Koh Kwan Siong).

Despite their small size and relatively slow rate of movement, seahorses play an important part in the marine ecosystem. Dr Adam Lim, a seahorse expert at the University of Malaya, explained that seahorses are “[an] important predator [that feed on] bottom dwelling organisms; much like how sharks are the top predator in the ocean. Removing either [seahorses or sharks] will disrupt the ecosystem as a whole.” On the Hantu reef, the most common seahorse spotted is the tigertail seahorse, a species that feeds by vacuuming plankton from the water and is thought to live to a maximum of 3 years.

The other species of seahorse that is commonly seen in Singapore is the Estuarine Seahorse, however those seahorses occur mainly along the northern shore in seagrass habitats and thus have never been documented on the Hantu reef.

How does such a fragile and slow organism survive in a sea teeming with predators? Dr Lim explains that “seahorses are blessed with [the] ability to camouflage by changing colours using chromatophores embedded within their skins. They carry a variety of chromatophores, enabling them to create different colours.” This is similar to the colour-changing mechanism seen in octopuses and squids. Additionally, Dr Lim notes that there are no known direct predators of seahorses, suggesting that blending in is indeed an effective defense mechanism for hiding from predators (I only wish that they had taught this in primary school).

When it comes to seahorses, one of the most talked about topics is seahorse sex, simply because of how unique the entire process is. Tigertail seahorses form stable pairs for at least one reproductive season and are suspected to be monogamous (however monogamy in wild animals, similar to monogamy in humans, is difficult to definitively confirm). More uniquely, seahorses (and the rest of the Syngnathidae family) are the only creatures on earth to have male pregnancy. After pairing off, the females transfer their eggs into the male pouch and wash their tiny pectoral fins off any further child-rearing responsibilities.

From here on out, male seahorses are entirely responsible for carrying the eggs to birth. When the eggs are ready to hatch, the male will explosively eject all 388 young (± 18) from his pouch into the wild unknown.

In 2015, a study conducted by Dr Lim found an even more unique trait about seahorses – they vocalize. Dr Lim and his colleagues found that seahorses produce feeding clicks by knocking bones in their head together and distress growls that are produced by some mechanism in their cheek. They think that these sounds may help seahorses communicate, but have yet to find the evidence to confirm this.

Threats

The IUCN Red List classifies the tigertail seahorse as ‘Vulnerable’ due to suspected global declines of the species by between 30-50%. Dr Lim explained that “Globally, the biggest threat to seahorses [are] 1) Direct exploitation, 2) Habitat loss and 3) Overfishing. In Singapore, there is limited fishing pressure along the coast and most of the threat to local seahorses comes from habitat loss due to coastal development. Large coastal constructions such as the Tuas mega-port could lead to the destruction of coastal seagrass and coral reef habitats, depriving seahorses of a home. There is no easy remedy for this situation, and balancing economic development and environmental protection has never been an enviable task. We need to be aware, however, that impact from development can be mitigated and/or avoided when residents (like you and me) actively participate and voicing our desire for wiser and more intelligent development designs and strategies (which includes asking the question, could there be a a more efficient and sustainable way to boost our economy?).

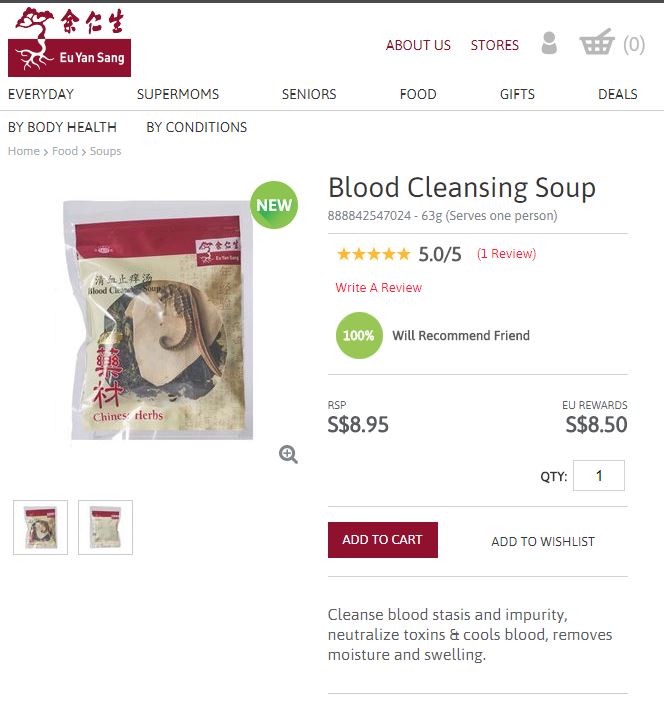

The impact that Singapore residents have on seahorses isn’t limited to within our national boundary. A study published in 1996 found that in 1994, Singapore imported 3600 kg of dried seahorses from India for medicinal purposes. While I couldn’t find any recent import statistics for seahorses, a quick search online revealed that TCM stores such as Eu Yan Sang still sell seahorses for medicinal purposes.

Seahorse is listed as one of the ingredients of the soup and likely contains tigertail seahorses, which are targeted overseas for the medicine trade.

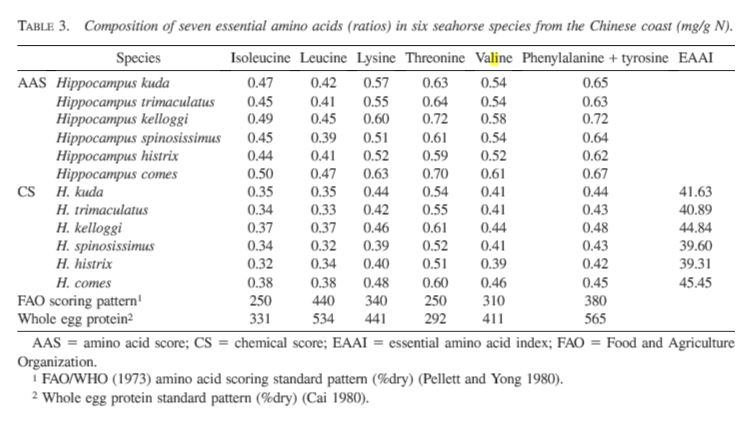

Consumers of seahorses believe that it is an effective cure for hives, skin infections, and even cancer. To date, there has been no scientific evidence to back up these claims (a study did find that seahorses had an impact on cancer cells in rats, but subsequent studies were never performed on larger organisms). Another study analyzed the biochemical composition of several seahorse species and found the presence of seven essential amino acids in the seahorses. However, the amount of amino acids was much lower than a regular off-the-shelf amino acid supplement.

The simple conclusion is that seahorses don’t have any unique chemicals that achieve any of the aforementioned healing benefits, and a simple way to protect seahorses in the region is to not consume TCM products that contain seahorses. After all, would you rather see seahorses like this:

Dr Lim also notes that average citizens who scuba dive can assist his colleagues at Project Seahorse with their iSeahorse Citizen Science initiative by reporting seahorse sightings. Divers can take a picture of the seahorses and measure and identify them easily through the available guides prior to online submission. Dr Lim added that “This simple yet important step helps syngnathid scientists to identify vital seahorse hotspots globally and work with various stakeholders in its protection.” More information about the project can be found at the iSeahorse page and on the IUCN-Seahorse Specialist Group website.

At the end of the day, much remains to be done to protect and conserve these fantastical marine organisms and Singapore residents have a part to play in protecting both seahorses on the Hantu reef and seahorses that live in the region.

Posted in

Posted in

content rss

content rss

COMMENTS